Lockback

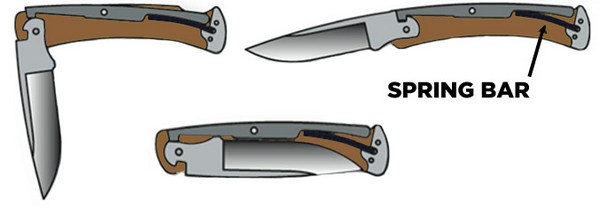

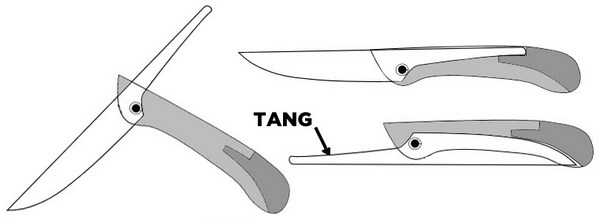

At their core, lockbacks (also referred to as back locks, spine locks or mid locks) are simply a derivative of the non-locking slipjoint (see below). The lock bar is pinned to the scales of the blade, pivoting in the middle, and a bent spring anchored further back in handle provides upward pressure behind the pivot point, pressing the front of the lock bar downward. In the closed position, the lock bar sits on a ramp in the bottom of the tang which provides a detent for opening.

When the blade is opened, the forward portion of the lock bar with its square protusion sits down into a matching square cutout on the top of the blade tang, locking it into position. The cutout on the tang matching the shape of the lock bar means that the lock bar has to be lifted out of the notch to release the blade. The spring bar thus keeps the lock closed until the bar is pressed from behind the pivot point against the spring tension opening the knife.

Tri-Ad Lock (Cold Steel)

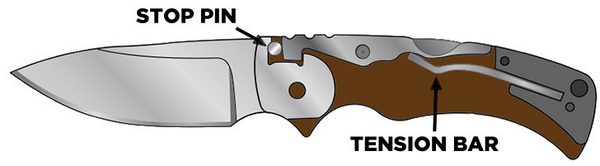

The Tri-Ad lock is a refinement of the lockback design by Andrew Demko, who designs for Cold Steel. It eliminates a common issue with lockbacks, which is play between the lockbar and the blade tang caused by wear. With the Tri-Ad lock, there is a stop pin which is anchored to the handles placed in between the lock bar and the tang. This takes the shock of lock-up off of the lockbar, reducing wear, as well as only requiring the lockbar to produce downward tension rather than downward and forward, which reduces fatigue on the lockbar.

The Tri-Ad Lock so far is exclusive to Cold Steel and to Demko’s custom knives. It makes a distinctive “clack” noise when opening and is a personal favorite of many enthusiasts for its solid feel.

Power Lock (Spyderco)

Spyderco’s Power Lock is another variant of the lockback, originally intended to increase lock strength on the enormous Tatanka with its 5″ blade. It uses a typical lock bar that’s mounted midway down the handle, which interacts with a counter-rotating cam which engages with the tang of the blade. This two piece arrangement helps to negate flex of what would be a ridiculously long lock bar if it were a single piece – the Tatanka stretches to more than 11.5” when opened.

Pros: Lockbacks are by design totally ambidextrous – since actuation of the lock is done along the spine, they don’t favor one hand over the other. They are also generally very strong – the lock bar is a lot thicker than a typical liner lock, being the same width as the blade stock itself.

Cons: Typical lockbacks suffer from wear on the mating surface of the lockbar after repeated opening and closing leading to vertical blade play – especially in a knife with an Emerson Wave opener. They typically aren’t the most “flickable” knives either, so the fidget factor is low. And one-hand closing usually requires your finger to be in the path of the blade closing, so care and familiarity is a necessity when closing the blade – especially considering the spring will force the blade closed past a certain point

Insider Tip: Look out for lint build up on the square cutout in the tang of the blade which can prevent proper lockup. Cleaning the tang out with a pocket screwdriver or compressed air regularly is a good idea to prevent this problem. Also keep an eye out for vertical blade play caused by wear on the lock face over time.

Liner Lock

Liner locks are probably the most common form of lock on modern folding knives – for ease of use, ease of assembly, and cost, it’s hard to beat a liner lock. They’re not the most exciting or creative lock but when executed properly they can be great.

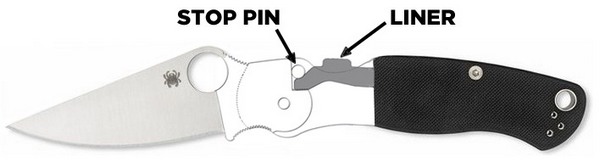

The basic design uses one of the blade’s liners, cut out and bent to create a spring effect, to engage the back of the blade tang when the blade is opened. While liner locks have been around for a long time, the modern implementation of the liner lock is credited to custom knifemaker Michael Walker, who made two important upgrades: using a stop pin anchored to the scales to precisely align the blade when open, and adding a detent ball on the liner lock to hold the blade closed, providing a snappy opening action – as well as added safety to keep the blade from accidentally opening.

Pros: Simple to use, inexpensive to make, familiar to almost anyone that’s ever used a folding knife, allows for a fast opening action thanks to the ball detent.

Cons: The user’s fingers are in the path of the blade when closing, not normally suited for heavy-duty use due to the thin nature of the liner itself.

Insider Tip: Look for where the liner engages relative to the tang of the blade – enthusiasts refer to this as “early” or “late.” An early engagement (closer to the locking liner side) is much safer than “late” engagement (towards the non-locking liner) as force on the blade will naturally move the lock away from the locking side. If the liner engages very late it can slide off of the tang and the blade can close on your hand. Also check for side to side blade play when locked open and if possible (i.e. if the knife has an adjustable pivot) tune any play out – it’s a balancing act with liner locks to get the pivot action just right. There are less worries about lint buildup than with backlocks.

Frame Lock

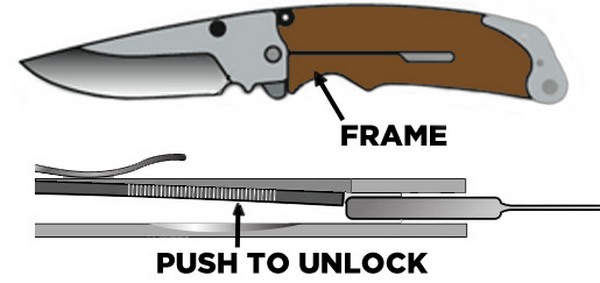

After liner locks, frame locks are probably the most common form of lock type on modern folding knives, especially at the higher end. The Frame Lock is sometimes referred to as the R.I.L. or Reeve Integral Lock, named after its creator Chris Reeve. It was first used in the Sebenza folder in 1990, still in production today after a series of revisions.

The idea is similar in concept to a liner lock, but stronger and simpler. The frame itself, at least on the lock side, is considerably thicker and forms the whole handle. A cutout along the axis of the spine has a relief cut out which creates inward pressure. When the blade is opened, the lock bar springs inward and engages the rear of the blade tang to lock the blade in place.

In almost every frame lock, a detent ball engages with a hole in the base of the blade to keep it closed, as well as providing tension for a snappy opening. A stop pin mounted above and forward of the pivot locates the blade’s end position when opened, also helping to eliminate wear on the lock bar. Simple in theory and strong in execution, the frame lock provides a large engagement surface and lots of mechanical strength to keep the blade open.

In recent years, a series of additions have been made by various inventors to improve the action and security of the frame lock. These include but aren’t limited to:

- Overtravel stop – invention of this is credited to Rick Hinderer. An overtravel stop is mounted to the non-moving portion of the frame, and the lock bar contacts it when it is pushed outward to disengage the lock. This prevents the lock bar from being pushed past it’s resting position which can quickly lead to metal fatigue of the lock bar and poor performance. On Hinderer-style overtravel stops it looks like the end of a bullet casing, but it some cases it is hidden from site entirely. These are sometimes referred to as “Lockbar Stabilizers.”

- Subframe lock – a patented invention (that has been successfully defended in court) by KAI, makers of Kershaw and Zero Tolerance knives, the Subframe lock is basically an inverted liner lock, where the scale itself is very thin and the frame/liner below it is thick. Access to the lock is by a cutout in the scale itself. A sleek looking minor variation on the framelock used in knives like the ZT 0777, Kershaw Camber, and some other unlicensed “tributes” by unscrupulous companies.

- Steel lockbar insert – the inventor of the lockbar insert is unclear, but over the past 10 years these have become more prevalent. They only apply to framelock knives where the lock side is titanium – the insert is a piece of hardened steel that bolts to the end of the lock bar and engages the tang of the blade. The reason for this is that titanium is a softer metal than steel, so over time engagement of the lock will wear the lock face, which can cause annoying “lock stick” or issues with engagement. Inserts are usually replaceable, but rarely need to be replaced. Some newer designs incorporate an overtravel stop into the lockbar insert on the inside of the handle, lowering the individual parts count of the blade.

- Rotoblock – invented by Molletta at Lionsteel, the Rotoblock combines a Hinderer-style Lockbar overtravel stop with a secondary locking device; the round insert is turned when the blade is open, physically blocking the lock bar from being pressed open until the Rotoblock is retracted.

- Ceramic ball-end lock – another Chris Reeve invention, currently used on the Inkosi and Umnumzaan, a ceramic detent ball on the inner “corner” of the lock face is both the detent as well as the interface with the tang of the blade – for the purpose of eliminating lock stick.

- Thumb stud/stop pin – some newer designs use the thumb studs as dual-purpose elements, both for opening as well as the stop pin to locate the blade. Grant & Gavin Hawk added a set of rubber gaskets to the thumb stud/stop pin to cushion the shock of flicking open the blade, which is now also used on the CRK Umnumzaan.

Pros: Extremely strong, simple construction, fewer parts.

Cons: Titanium is prone to galling and creating lock stick after flicking the knife open repeatedly (which is countered with a lockbar insert, increasing weight and complexity), action is very dependent on correct pivot tension, not ambidextrous at all.

Insider Tip: Look out for wear on the lock face that shows up as odd movement. Sometimes this can present as vertical lock rock (bad) or lock stick (annoying), or if the geometry of the lock face isn’t quite right it can make the lockbar walk off the tang under pressure. 99% of the time frame locks are rock solid but they do require attention. Also keep in mind that if there is horizontal blade play at the tip, there’s also blade play on the other end of the pivot – at the tang/lock face.

Compression Lock

The compression lock can be thought of as an improved, inverted liner lock. It was developed and patented by Spyderco, and known primarily for its use in the popular Paramilitary 2 folder, although application of this excellent lock is starting to expand.

It also uses a split liner that springs into place when the blade opens, but it is along the spine of the blade, and opens into place between the tang of the blade and the stop pin. This makes it both stronger than a typical liner lock as well as easier to operate, since your fingers are never in the path of the blade when you close it.

In addition to increased strength and safety of operation over a liner lock, a compression lock also has a higher “fidget” factor than a liner lock, owing to its ability to be swung open when the lock is pushed open similarly to an Axis Lock. The one handed ease of operation of the compression lock has become the bane of existence of many a knife nut’s spouse – from anecdotal evidence.

Pros: Stronger than a liner lock, safer to disengage with no fingers in the path of travel, high fidget factor, ease of use

Cons: Requires precise machining tolerances, susceptible to tension tuning in the frame of the blade, may wind up annoying your spouse

Insider Tip: A tip for Paramilitary users: when adjusting pivot tension, equally tighten the pivot pin down on both sides, then slightly loosen the stop pin (a quarter turn or so) to achieve a smooth action with no blade play.

Axis Locks and Derivatives

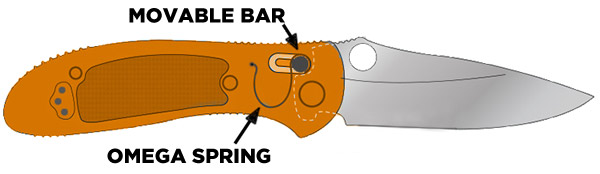

The Axis lock is the shining star of Benchmade Knife Company, and using one for a few minutes will show you why. It’s an addictively fun lock, with many practical benefits. The invention of the fertile minds of Bill McHenry and James Williams (who collaboratively design for Benchmade, usually referred to as McHenry & Williams) the Axis lock first debuted in 1998 on the 710 (almost 20 years old now!) and has spread across the majority of Benchmade’s lineup.

It’s simple in execution: a steel bar rides in slots cut in the handles and liners, passing through both. Two “omega” springs (named after their shape, like the greek symbol Ω) provide equal tension on both sides of the bar. There is a notch cut into the back of the tang, and when the blade opens the springs force the bar onto the notch. A stop pin locates the blade to increase reliability. The Axis Lock is also used by Ganzo in China, seemingly without concern to the lock’s existing patent in the US – sadly a common problem with IP rights in China.

Due to Benchmade’s patent, there are also a number of different variations of the axis lock, which all operate on the same principle but use different style components to suit the designer’s needs. They all use a spring to force a solid object on top of the blade tang, locking the blade in place.

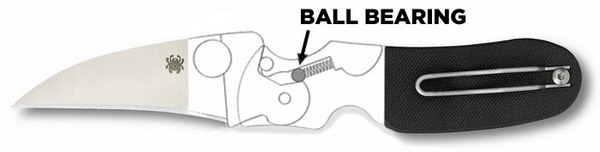

Ball Bearing Lock (Spyderco)

Invented by Sal Glesser and refined by Eric Glesser, the Ball Bearing Lock is a simplified take on the Axis Lock concept. As is obvious by the name, a hardened steel ball bearing engages with a ramp on the tang of the blade, but as opposed to the Axis Lock’s dual Omega spring arrangement, a single coiled spring anchored to the handle provides tension. It can either be naked or caged, like the lock on the popular Manix 2. A very fun lock to play with after a proper break-in period.

Arc-Lock (SOG)

The Arc-Lock is another variant of the Axis Lock idea implemented by SOG Knives. A metal block (shaped approximately like a peanut) is mounted to a pivot that is parallel to and behind the stop pin. Curved springs force the block downward in an arc when the blade is opened or closed, engaging the back of the tang into a locked position when open, and creating opening tension when closed. It’s very strong and slick when used in the Vulcan series, although implementation in SOG’s cheaper knives like the Aegis leaves something to be desired.

Pros: Axis locks and their derivatives are usually ambidextrous (the exception being some SOG models like the Aegis), they keep your hands out of the closing path of the blade, they’re easy to close – usually only requiring pulling back against the spring and flipping the blade closed with your wrist, and they provide another option for opening – pulling back on the lock and flipping the blade out with your wrist. They are also quite strong depending on the scale materials that the locking object presses against.

Cons: Springs can break, especially Benchmade’s Omega springs, much more easily than torsion springs like those used on lockbacks and liner locks. There are a lot of moving parts, all of which are susceptible to dirt buildup. Benchmade’s Axis Locks are very prone to horizontal blade play, and require a hyper-delicate adjustment of the pivot to balance blade play with a smooth action.

Insider Tip: Pay attention to the springs that actuate the locking mechanism on the Axis or similar devices. If the lock begins to engage or disengage unevenly it may be a sign the springs are about to fail.

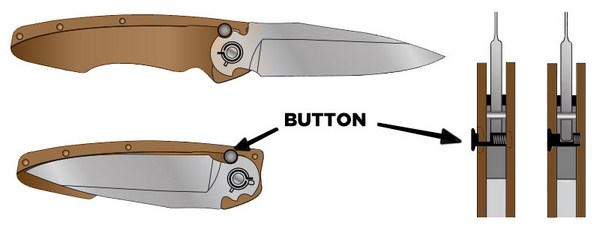

Button Locks

Button locks (or plunge locks) are traditionally the actuation method of an automatic knife – pressing the button releases the blade, and coiled spring tension fires the blade open. Once the blade is opened all the way, the plunger (the round internal component of the button lock) engages a cutout in the tang of the blade, holding it open. With an automatic knife the button lock locks the blade open as well as closed, preventing the knife from accidentally opening unless the button is pressed.

Lately, manufacturers have started using the button lock on manual folders (like William Henry and Hogue Knives), the difference being that the engagement point of the blade tang is changed to create closed resistance rather than a locked condition – using a ramp shape instead of a totally round cutout. This creates an “opening detent” like the small ball bearing does on a frame/liner lock.

Pros: Very strong locking strength, hand is out of the path of the blade when closing, fun to play/fidget with

Cons: Difficult and expensive to manufacture correctly, not ambidextrous, police may assume you have an automatic knife even if it isn’t.

Insider Tip: Research the legal definition of “push button knife” and how loosely it’s enforced in your locale. Can you hold the button open and flick the knife with your wrist? Also, watch out for lint buildup on the blade tang cutout.

Collar Lock

The collar lock (or ring lock) is undoubtedly most recognizable on folding knives from the French manufacturer, Opinel. Operation is simple – you lock the blade in place by twisting the ring or collar so that the blade in unable to move. To open or close the knife you twist until the slot aligns with the blade allowing it to move. While lacking in any complexity, the collar lock is surprisingly effective.

Pros: Pure simplicity makes for low cost manufacture and ease of operation

Cons: The collar or ring can stiffen over time which inhibits smooth operation of the folding blade.

Insider Tip: The ring often needs maintenance which is normal after prolonged use. If it turns too easily, use pliers to tighten. Conversely, if it’s too tight, carefully pry it apart with needle nose pliers. Adding a small drop of lubrication is recommended.

![]()

Non Locking Folders

Knives are stored in purses, which contain a lot of corrosive elements. These may become difficult to open over time unless you make a point to regularly oil the pivot and clean out dirt.

Not all folding knives actually lock open; in fact, in a lot of locales a locking knife simply isn’t legal to carry. Residents of the United Kingdom for example are legally prohibited from carrying a knife that locks in the open position (defined as requiring a separate action like pressing a button or similar to close the blade). It’s also inadvisable in other places, even if it isn’t expressly illegal.

For instance, civilians in New York City can be charged with a felony if they are found to possess a knife which can be opened via gravity – even if this includes ridiculous techniques such as pinching the blade and shaking the handle open. Some say it’s a favorite past-time of the NYPD, or a useful technique for generating probable cause for a search.

So if you cannot legally possess, or simply don’t want to carry a locking knife, what are your options?

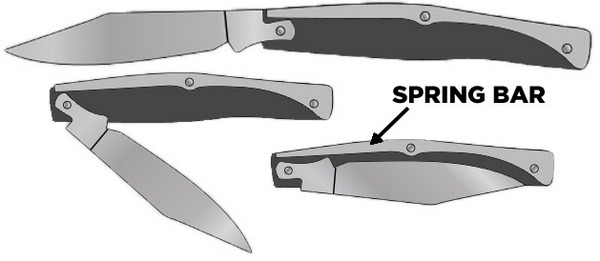

Slip Joints

If you’ve handled a Swiss Army Knife you’re already familiar with a slipjoint. A slipjoint provides a modicum of safety to folding knife users without actually having a locking mechanism. In simple terms, a slipjoint is a spring that holds the blade open and closed. The spring sits along the spine, anchored to the handle midway down, and it presses against the bottom of the blade tang to hold the knife closed.

As you pull the blade open, the spring flexes upward. Once fully opened, the spring “snaps” down into a rectangular relief cut into the top of the tang, providing a force which keeps the blade open. You have to overcome the spring tension to close the blade, so it doesn’t just flop around, but it isn’t actually locked. There can also be another “flat” spot ground into the tang between the open and closed position which provides a half-stop, but not all slipjoints include this.

Pros: Simplicity, reliability, easy of manufacture, satisfying “snap” noise when opening and closing, legality in restricted regions

Cons: Doesn’t actually lock, must use both hands to open

Insider Tip: Be aware of lint build-up in the square notch on the tang of the blade. If enough “gunk” builds up on the notch, the spring won’t engage all the way and you’re more likely to have it close by accident. Also, many slipjoints like Swiss Army Knives are stored in purses, which contain a lot of corrosive elements. These may become difficult to open over time unless you make a point to regularly oil the pivot and clean out dirt.

Friction Folders

Friction folders have been around for hundreds of years and are less complicated – the user’s hand is the lock. The tang of the blade when closed extends outward away from the spine, which can be used to open the knife somewhat like a forward flipper. When open, the tang lines up with the spine of the handle and when you grip it, your palm itself prevents the blade from folding back into the handle. There’s not much more to it than that.

Pros: Simplicity, ease of manufacture, legality in restricted areas, no need to worry about weak springs

Cons: Doesn’t actually lock, can be awkward for pocket carry

Insider Tip: The tension on the pivot is all that controls how easily the knife deploys, so be aware that the possibility exists that the blade could creep out under certain circumstances